Author: Bob Morse

Over the past dozen or so years, the software industry has transitioned its pricing regime from upfront license purchases with a relatively small recurring maintenance fee (“license + maintenance”) to subscription pricing. As part of that evolution, every software company did an equivalence calculation to determine how to convert an up-front license payment into a series of ongoing subscription payments. This change to a string of payments over time made software companies much more “bond-like” in their economic character.

However, during the past 12 years of that transition, inflation averaged only 1.7% per year. Inflation today is radically higher, around 7.0%. This means that the entire software industry repriced its business model using a discount rate that is now out of date. And, as we all know, when rates rise, bond prices fall. How does this impact the fate of subscription pricing? How far off track is it now, and does it remain an optimal model for software companies?

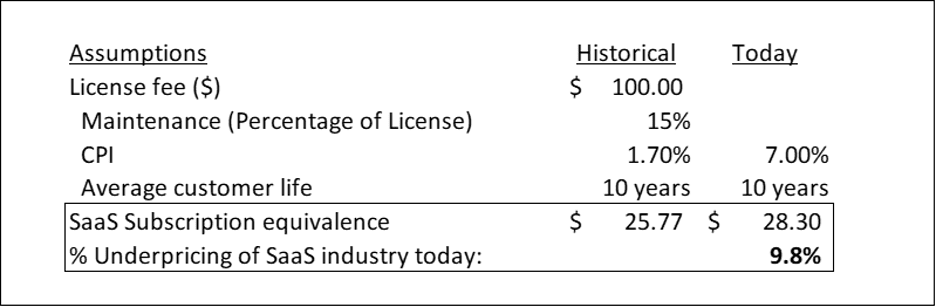

To get a sense of the mispricing, let’s look at some simple net present value (“NPV”) calculations.

Assuming a ten-year customer life, and a historical norm of maintenance equal to 15% of the license fee, the above calculation shows that—everything else being equal—the jump to 7.0% inflation means SaaS prices are around 10% lower than they should be, if they are meant to be of equal present value to the old license + maintenance pricing. In other words, SaaS companies would first need to raise prices by 9.8% to be back on par with the old license + maintenance model, and then raise prices further to pace inflation. It’s a tall order.

Certainly, numerous factors make this analysis far from an exact science. Longer customer lives, or lower historical maintenance fees, for example, would mean a business has even further underpriced its subscription contracts. On the other hand, the shift to subscription pricing has generally been more attractive to lenders and the capital markets, arguably reducing the weighted-average cost of capital for SaaS companies versus license + maintenance companies. Finally, the shift to SaaS was not only a change in pricing, but also a change in delivery from customer premise installation to over-the-internet access. This change in delivery had vast implications for product innovation and customer engagement. Yet despite these complicating factors, we believe the conclusion holds: Subscription software companies have become more bond-like in their economic character (streams of income over time), and as a result, the present value of a SaaS company will decline when rates rise, all else remaining equal.

Given this situation, we’ve been asked by several investors whether we intend to consider shifting the revenue models of our portfolio companies to have larger up-front components (reverting towards license + maintenance), or whether we plan to stick with revenue models that focus on long-term subscriptions. It’s a fair question, as all but one of the software companies in the Strattam portfolio today sell through a recurring subscription (SaaS) model, and that one company, MHC Software, is actively shifting its revenue mix from a license + maintenance revenue model to a SaaS model.

Our answer is straightforward. Despite a rising rate environment undoubtedly reducing the NPV of a recurring cash flow stream, we still favor subscription revenue models over a traditional license + maintenance model.

We have three reasons for this decision:

- At the time we invest, our target companies are nowhere near optimal product pricing. Because they were bootstrapped businesses and needed cash in the door, they have tended to charge a lot for up-front implementation services in exchange for lower ongoing subscription fees. Founder-led businesses are also notoriously reluctant to raise prices, often for emotional reasons related to customer loyalty. As such, shifting more revenue into subscription fees and re-setting pricing is one of the highest-impact actions Strattam can support. Case in point: a few years ago, we invested in a company that had not raised prices in a decade. We worked with the company to conduct a detailed pricing study, met with the usual resistance (one co-founder said, “I just don’t think that will work for us,”), and eventually reached consensus on a new “good-better-best” pricing structure. From the first quarter to the fourth quarter of 2021, average prices from new customers rose from $759/month to $1,366/month, an 80% increase, while also growing the total number of new customers added.

- We seek to invest in companies that provide mission-critical software to their end customers, most of whom also have high switching costs—so once they have invested in a provider, they tend to stay put. These factors result in pricing power. Moreover, in addition to raising list prices, mission critical companies can also provide for annual price escalators in their subscription contracts with customers. While many can, in practice, fewer actually do include and enforce escalators, another opportunity area. Continuing the bond analogy, the ability to raise prices is what changes the “fixed-rate” character of software subscriptions to a “floating-rate” character (and the best SaaS companies have wide latitude in setting the rate).

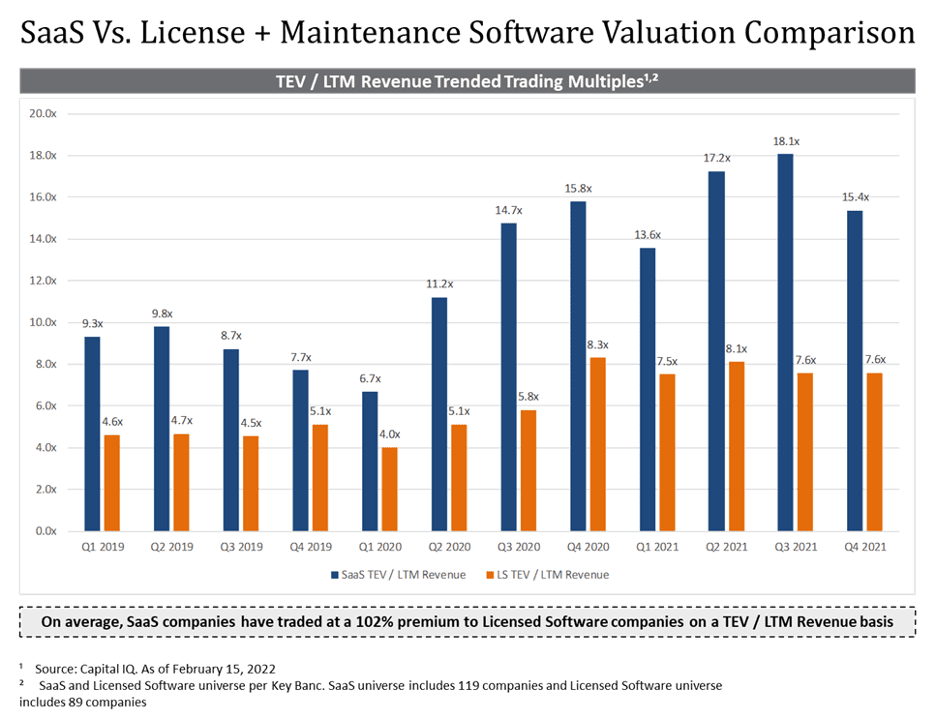

- SaaS companies trade at much higher valuation multiples than license + maintenance model companies. We believe that the level of premium ascribed to the subscription model companies more than compensates for the rising rate impact. As shown in the chart below, over the past two years, investors in the public markets have been willing to pay approximately twice as much for SaaS companies as they have for license + maintenance companies on an EV / revenue multiple basis. The higher multiples ascribed to SaaS businesses with higher revenue quality dwarf the impact of rising rates on the NPV of their revenue streams.

Raising prices is one of those things that is much easier said than done, primarily due to a powerful emotion called fear—specifically, the fear of upsetting and losing customers in the process. This is why we asked a partner from Simon-Kucher, a leading pricing consultancy, to be the keynote speaker at our CEO Conference last year. As he explained to our CEOs, raising prices is as much a psychological challenge as it is an operational one. All our portfolio companies are executing some form of price increase in 2022, and my colleagues and I are committed to providing our founders and CEOs with the support they need—moral support as much as technical—to implement these changes.

In summary, the shift in pricing over the past decade has made software companies much more bond-like in character, and as such, they are not immune to inflationary pressures. Inflation has changed the trade-off equation between up-front payment and payments over time. Adapting to this new reality is a test of both external facts (“Will my customers accept a price increase?”) and internal fortitude (“Do I dare raise prices now?”). It is a challenge many of us are facing for the first time, and certainly for the first time in this phase of our careers.